In the early 1960’s we just could not get enough of baseball. We were baseball nuts, and we loved the New York Yankees, at least in the spring and summer months before the hockey season started. And even at the end of September and into early October when the World Series arrived, we had to watch the Yankees. They were always in it, and they were so good! Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Elston Howard, Whitey Ford, Ralph Terry, Bobby Richardson, Cletus Boyer, Tony Kubek, even Yogi.

We knew their names and all their year-by-year stats. We pored over the post game stats published in the London Free Press to keep track of how each Yankee player was doing. We even developed our own baseball card game using a standard card deck to play all 162 games the Yankees played during the year. We watched them on TV (or listened on the radio) when they played. We loudly cheered out the back door when a home run was hit (often) or when the Yankees won the game. We wore black arm bands for a week after Bill Mazeroski single-handedly destroyed our team in the bottom of the ninth in the final game of the 1960s World Series.

We tried to emulate the (winning) Yankee manner and success when we played the game ourselves. We called ourselves the “London Yankees” (since we were, naturally, from London, even though London was a Detroit Tigers town for most residents who followed baseball).

We all wore the same London Yankees uniform. Foremost on every player’s head was a dark blue baseball cap with the letters “NY” emblazoned on it (we got them when Steve went to a ball game in Detroit and his mom picked them up on sale. Unfortunately for some of our group, seven Yankee hats was all they had. Steve kept two, so five others got to wear the coveted hat. Those unlucky players who did not get the MLB sanctioned hat had to draw the letters on their own blue ones).

We each wore a light blue long-sleeved sweater, cut off at the elbow. Surprisingly in those days sweaters were always the same colour – blue. The cutoff sweater represented the under-shirt that extended out from under the team shirt. Wearing the undershirt was unmistakably different from other kids’ baseball “uniforms,” for sure. It made us the London Yankees! But the undershirt was also extremely hot next to the skin in the summer months.

Over the cut-off sweater undershirt, we wore a white tee shirt crested with “Yankees” across the chest. Ken’s dad got the “Yankee” lettering and shirts for us as his eight other brothers (no girls in the family except Ken’s mom) were in organized baseball and played all over Southern Ontario. The New York Yankees were, of course, the entire family’s favourite team and once a year they packed into their Rambler – an eight-passenger station wagon – and made a pilgrimage to Yankee stadium. My dad used to say that the Pert Rambler was the biggest car he had ever seen.

We also wore cream-coloured pants. To kids they were known as “summer cream.” That colour pant was worn by all kids going to school from April to June. No shorts were allowed at school.

On our feet we wore blue socks to match our sweaters, and of course, we all had black baseball spikes that we bought for everyone at the local sports store with money collectively earned cutting lawns for folks in the neighbourhood.

I must say, we always looked very impressive when we took on other teams. Those teams often wore shorts and rag-a-muffin tee shirts and uncrested hats. Unlike the London Yankees, they had nothing that tied them into the “team” look. Yes, we looked exceptionally good! But unfortunately, we also must have smelled disagreeably, being at an age when perspiring was a relatively new phenomenon and wearing deodorant was not something you did. A sweater under a tee shirt and long pants was definitely a warm outfit, particularly in summer.

It was not just our consistent dress and team skills that distinguished us as a baseball team. We were baseball fanatics. We played baseball non-stop during daylight hours. On weekends we would play all day (except for breakfast and dinner times). We brought our own peanut butter and jam sandwich lunches when we played. On weekdays we would get home from school and bike to the diamond as quickly as possible. When darkness came, we peddled home by streetlight.

As a group we were incredibly well organized (it was the same during the hockey season when we built the rink and played hockey in Northey’s backyard) and built our own baseball diamond at Kiwanis Park. Every spring we used Dave O’Neil’s father’s gas-powered Toro lawnmower to remove the grass and weeds that were trying valiantly to take over our baseball diamond. You had to wrap the rope around the pull socket of the lawnmower and then pull for all you were worth, but it started (for Dave) every time, and it could cut any height of grass.

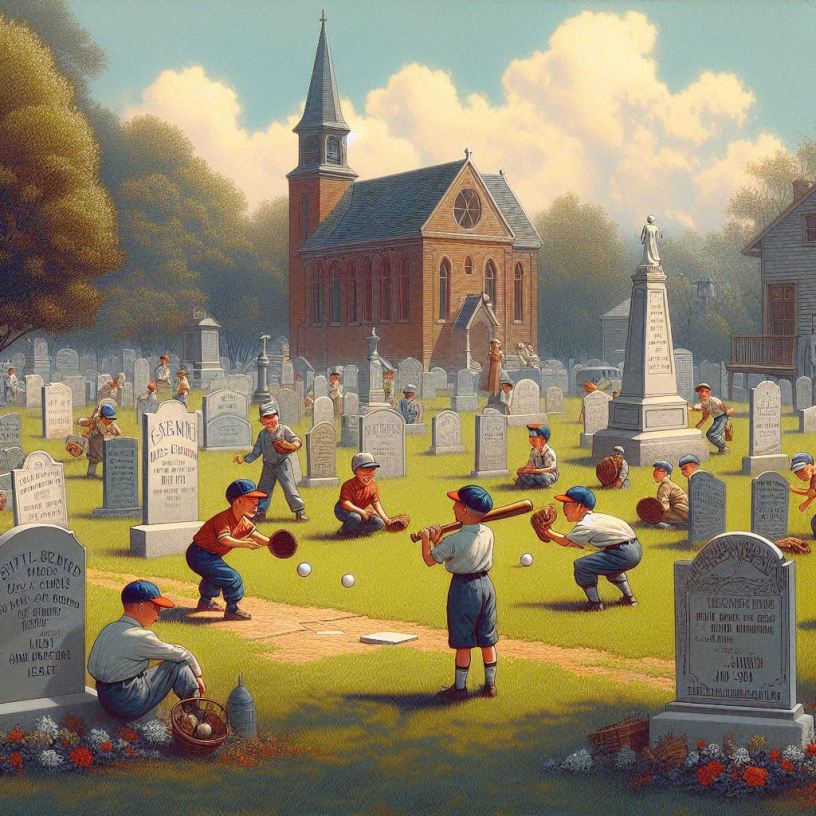

Our baseball diamond was located at the far end of Kiwanis Park next to the cemetery. We chose that location because it did not flood in the spring like the other areas near Pottersburg Creek. We also liked the cemetery location as it had an “L” -shaped chain link fence border that conveniently served as the outfield boundary beyond which home runs were automatically scored. The awkward part of the cemetery fence, though, was the need to climb over it to find the ball among the tombstones after a home run. Eventually we cut a section of the fence near the Trafalgar Street corner to crawl through to retrieve the ball more quickly. As a sign of respect for the cemetery residents, though, we diligently wired that fence opening together again after each game.

Our foul lines were carefully marked, initially with a string line stretched from home plate to the cemetery foul pole. It was then covered with a chalk line using a roller Earl obtained from his football team during their off-season. To avoid the necessity of having to chalk regularly, we spray painted the lines. Mrs. McCready made us bases out of flour bags, filled them with small glass beads, and then stitched over those bags with a hardened vinyl bag they used in the laundromat where she worked. On the bottom of each bag was sewn a “handle” that was held in place by metal pegs that Mr. Tiedeman crafted for us. Each base was spray-painted as was home plate which was an official size that Ken’s brother Rudy had made in shop class. You could see the foul lines, home plate and the infield bases from hundreds of feet away. The immaculately cut grass infield and outfield made it look like a real ball field.

Of course, the pitcher’s mound needed to be resurrected after each snowy winter with fresh wheelbarrows full of creek sand left over from the annual Pottersburg creek flooding. This sand proved remarkably resilient throughout the year, even when baseball cleats were used. On the mound we placed the official 6” by 24” “rubber” which we pinned into the mound with long metal pins. Bob T’s dad, who worked at Empire Brass, found us a piece of extremely stiff rubber, drilled two holes in it and attached two long metal spikes to hold it down. We spray painted it as well to ensure pitchers did not take their foot off the rubber when pitching.

Behind home plate we “borrowed” a snow fence that the farmer next to the cemetery had installed one winter but never used after that first year. To be honest, that snow fence detracted from the beauty of the rest of the diamond, but we needed something to catch wayward balls as several feet behind home plate the ground sloped quickly into Pottersburg Creek. A ball retrieved from the fast-flowing creek was never the same afterwards.

There was a distinct thrill about hitting a home run over the cemetery fence but there were not many of us who could accomplish the feat. Unlike the Yankees, we were not home run hitters but knew the value of singles or well positioned doubles to score runs. And not wishing to brag too much, I was a fairly good pitcher. No fastballs but a good sinking curveball and a bat choking slider. They had a tough time hitting my “junk.”

Imagine, if you can, fully uniformed kids playing endless innings of baseball. Imagine, too, if you can, trying to close off the last inning before it gets too dark to see. Picture Earl McGuffin hitting a pitch that we knew was going over the fence…the cemetery fence. We all knew then it was time to find the ball and go home. As he ran around the bases jumping merrily, two of the Pert brothers and Steve G. crawled through the fence opening to begin looking for the ball. We could hear them giving instructions to look over there or maybe there but clearly this ball was not going to be easily found. We all climbed through the fence and began searching among the tombstones. No luck, and it was getting so dark. We could hardly see. Bob F. said he was not giving up as he had just bought that ball the previous day for $4.00. Whoa, that was a lot of money to spend on a ball. Is it any wonder McGuffin hit a home run with that new expensive ball!

As we looked for the ball it got darker. And damp fog from the Creek started to envelop the area. I started to panic, not knowing where I was going. I hit my knee on a tombstone, and it really hurt. I could hear voices but saw no one. Then suddenly, I heard it. We all heard it. A low-pitched sound that suddenly became louder and then morphed into a higher pitched whine. The sounds grew louder and more pronounced.

A group of strong supporting friends should really have little fear of even unexplainable noises. But in a dark foggy cemetery? I heard Dave Monk yell, “I’m getting out of here.” He sounded panicky but more so when he exclaimed “Where’s the fence cut-through?” “Where are you,” said someone. The moaning noises started again. Nine frantic kids, looking for the cemetery fence, bumping and tripping over tombstones. By now I was scared. I do not think I was alone in that feeling. Suddenly I felt the chain link and climbed over it. I saw the foul lines and tried to yell to the others to come this way. “Where are you” was repeated endlessly.

I do not know how we all got out and found our bikes. I just recall how dark and spooky it was. In the distance I could barely see a faded streetlight on Trafalgar Street. We did a little attendance check, got on our bikes, and rode toward that streetlight, eventually finding the road. It is amazing how fear can make you more confused, but it took us a long time to get home. I went straight to bed, disregarding my mother’s “Is everything okay?”

Next day at school we got the entire team together at recess. Nobody said they had not been scared. We all agreed that we would not play again at the diamond until next weekend.

When you come from a family of nine boys, and word gets around from brother to brother, it does not take long to decide to investigate the strange happenings at the cemetery. Pert family on the case! All the Pert boys banded together in the early evening to go to the cemetery. Carrying flashlights and baseball bats (just in case) they had to find out what was going on. There was the expected talk about ghosts or zombies: they must have been annoyed by the baseball team stomping on their domain.

Ron, the eldest Pert, eventually found the real source of the noises. Next to the fenced cemetery area was a farm which in an urban community like ours was generally ignored. Bravely, Ron walked around the farm periphery by the cemetery fence in the darkness, guided by his flashlight. Suddenly, he caught the movement of several cows, some with calves, as they came out from the strip of farmland on the far side of the cemetery, a small section that was quite close to the baseball diamond. As they walked, the mother cows would often moo at their calves, to get them to move closer to the herd.

Gathering the Pert clan together, Ron asked Ken if that was the sound he heard. The youngest brother laughed and admitted it seemed remarkably similar. They all concluded that this was what we had heard that fateful night when we were scared of potential cemetery apparitions.

Ken was good enough to tell us the “true” story the next day. He had that smug look on his face when he told us what they had found, suggesting that he was never really afraid.

The desire to return to baseball was obviously stronger than the lingering fears of the cemetery at dark, so we did return to playing on our “London Yankees” diamond. But the World Series of 1963 put the death knell onto our team. Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale blanked our heroes in four straight games. By that time, hockey was suddenly was more interesting, and we lost our zeal for baseball, as it turns out, for good.

Next spring some of us were starting to be fascinated by a new sport – golf. When Dave announced that the old Toro lawnmower no longer worked, our interest in baseball seemed to fade. We followed the Yankees, but we did not play much. The grass and weeds eventually grew over the “London Yankees” diamond.

I am sure, though, that even today, the neighbourhood kids avoid that cemetery at night.