A Mill Pond?

Recently someone asked me where the mill pond was in Berwick. It’s a little community about three kilometers south of where I live. I pass through that village regularly, but I have never imagined there was a pond there at any time.

It got me to investigating the history of that village, which like so many neighbouring communities in Eastern Ontario, is quiet and easily missed when travelling along the major thoroughfares. It turns out there is a lot of interesting history there, including the mill pond.

Berwick – A Snapshot of Today

Berwick is about 45 to 50 minutes southeast of Ottawa. Today it has about 150 people. It has a long history in this area, going back to the early 1800s. It has gone through boom times and is now continuing without much growth. Most residents commute to Ottawa or work home-based as trades folk servicing nearby farms, businesses, and residences. Like so many small communities in this area, though, family linkages remain strong.

A Contribution Beyond Its Size

This small community exerts an importance well beyond its current size, as today, and for more than 175 years, it has been the location for the seat of municipal governments, initially for Finch Township and in recent years, for North Stormont Township.

In an early atlas of Eastern Ontario[i] (1879), the authors remarked that Berwick “is evidently one of the “has beens”, meaning it had seen greater prominence in earlier times. As they go on to note: “…its present status is not imposing”. Certainly its early history is significant for this region, but lots happened in Berwick after that atlas was published.

The First Settlers

There is some recorded history about how settlers eventually got to Berwick[ii]. Suffice to say, that early access was difficult.

In 1803, Allan (Glen Payne) McMillan led a group of McMillan and Cameron family members from Scotland on a journey to Canada to find a new home, and ultimately, they worked their way to Finch and to Berwick in the new Canadian jurisdiction of Upper Canada.

The voyage record is not available, but it appears to have taken much longer than an ordinary trip. A 13‑week Atlantic crossing in Allan (Glen‑Payne) MacMillan’s time was not just a long trip — it was a test of endurance, faith, and sheer determination. As the normal crossing time would have been 8-9 weeks, no doubt there were some eventful and unhappy stories surrounding that trip.

The trans-Atlantic journey didn’t end at Montreal. The settlers still had to go many more kilometres inland to reach Kirk Hill, a Gaelic community, which for Scottish immigrants was often their first key stop. To reach Kirk Hill, Allan (Glen‑Payne) MacMillan’s settlers had to row and haul batteaux up the St. Lawrence, portage around dangerous rapids, land at Cornwall, and then walk for days on modest trails through unbroken forest. Only then did they reach the Highland community at Kirk Hill — the first foothold for the families who would later begin their new immigrant life as residents of the area near Finch and Berwick.

From Kirk Hill, several family members — including Camerons and MacMillans — moved westward into Finch Township. MacMillan himself likely remained in Glengarry, but his people helped anchor the early farming community that existed in the Finch/Berwick area long before Berwick became a village. The original settlers traveled over crude roads and trails, with their supplies on their back and children alongside. It was a monumental effort and when they arrived they had to build crude lean-tos or cabins for shelter. With few sources of supplies from the outside world, their life was hard, and winters were particularly cruel.

To obtain land for settlement, McMillan was required to establish lots and provide a tenure layout, and to build roads before being recognized as a settlement. The British would then allow him to have license to the land his group would settle. Records indicate that he hired a surveyor (Mr. Bower) to lay out a lot plan for the community.

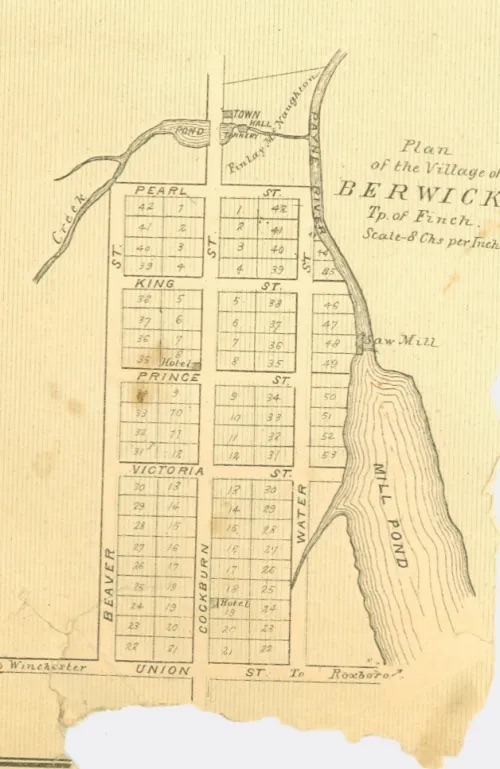

This map shows the original settlement survey and subsequent development that transpired after. It was not until four other Scotsmen settled in present day Berwick that the settlement was established as a true community.

The Cockburns, initially from a community called Berwick in Scotland, established a sawmill on the Payne River, blacksmith facilities, and a general store. Their enterprising spirit helped to encourage others to take up residence there and for the settlement to grow. Originally the community was called Cockburn Corners but was changed by the Cockburns to recognize their Berwick home in Scotland.

Eventually a Post Office was established, the spark that would link Berwick with the more populous areas in the south. A Post Office provided access to supplies for expanding the village, but it also provided another important tangible benefit – access to news from the “outside world”.

Remarkably, despite its early growth, the current village layout and the original settlement plan, as Mr. Bower drafted, remains virtually the same today as in the 1830’s.

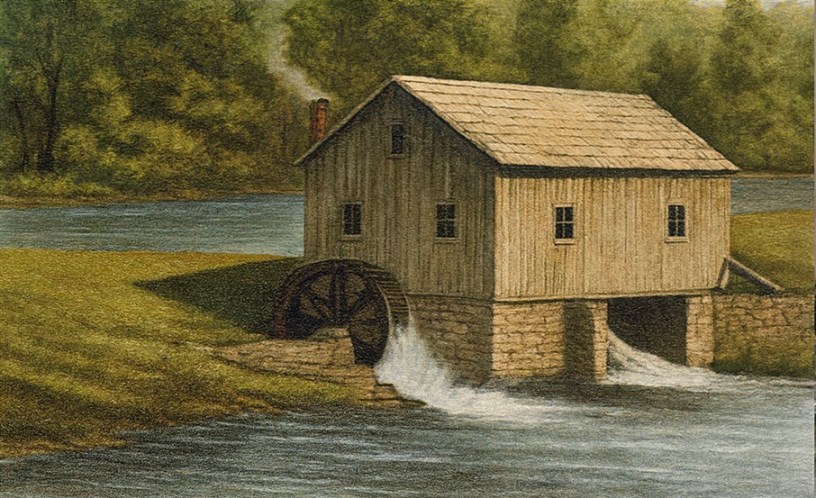

A Saw Mill and a Mill Pond

What we see in that early survey map is a sawmill and a mill pond.

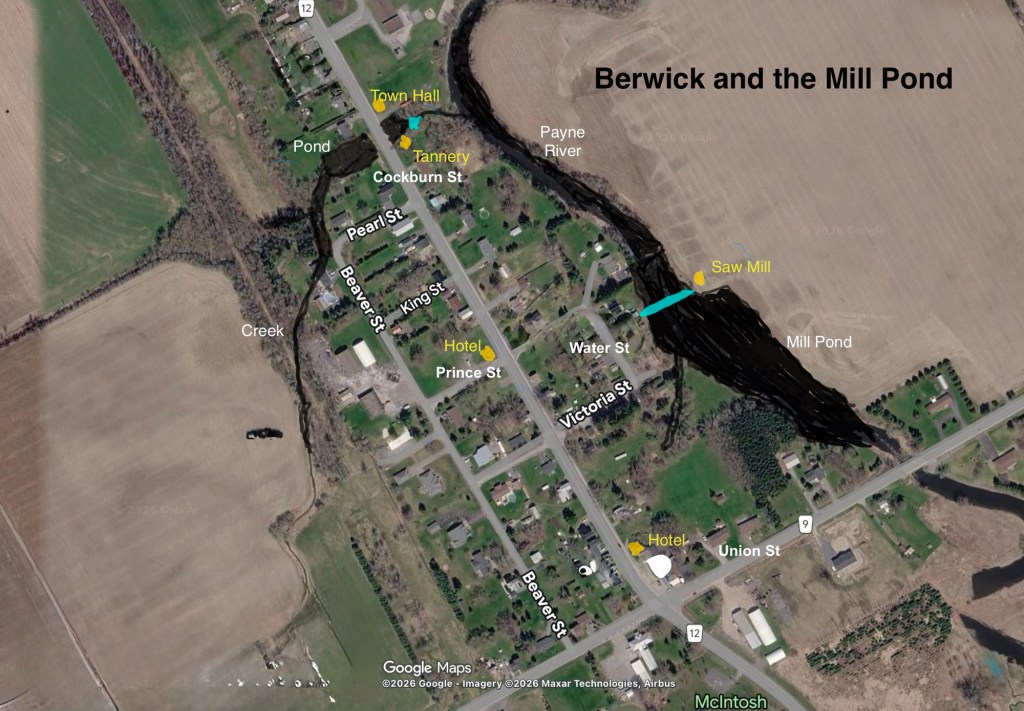

That pond was used to supply water power to Adam Cockburn’s sawmill, one of the very first industrial operations in the hamlet. The Cockburn brothers—Adam, Peter, James, and Isaac—were the real founding settlers of Berwick. Adam built the water‑powered sawmill on the Payne River, and the mill pond was the reservoir that fed it. His brothers set up the supporting businesses for the community.

The sawmill operated seasonally from March to July. Trees from surrounding forests were converted to sawn lumber and squared timber. During the rest of the warmer months, shingles were cut to be used to cover the roofs of homes. In the early spring the logs and sawn timber would be pushed along the ice on rafts atop the ice on the Payne River, or afloat in its melting waters.

The wood would be transported first to the South Nation River near Crysler and then on to the Ottawa River (near Plantagenet) enroute to Montreal. It was a long, difficult and dangerous task, but Montreal was anxious to receive the lumber, some of which was used there in Quebec (Lower Canada), but other lumber was exported, likely to Britain. There was an insatiable appetite for Canadian lumber for boat building in Britain at that time.

Modified Google Satellite Image of Key Landmarks in Berwick (1850)

Berwick Continues to Grow

As the village grew, so did its trades. A blacksmith was important to the local economy and there were two. There were also three buggy makers, a wheelwright, a tin smith and a shoemaker. There were general stores, butcher shops, and bakeries. These shops filled the area around the tannery on the tributary creek of the Payne River. (Still visible today).

Nearby, the Berwick Town Hall was constructed and is shown on the early map just east of the tannery off Cockburn Street. In 1850 Berwick became the Finch Township municipal centre and the Town Hall was used for township meetings and administrative purposes.

The Town Hall has an interesting political as well as community history, too.

Apparently when Council members met one winter day the original Town Hall was so cold they kept on their coats despite the fact two stoves were burning wood to heat the building. Snow apparently was evident blowing through the floor cracks.

The politicians then addressed the immediate pressing issue of replacing the Town Hall. Cleverly they reckoned that Finch had overpaid its taxes. The overpaid monies would then be available to help in constructing a new Town Hall. When the Women’s Auxiliary offered to provide additional funding and guarantee the work, the politicians rose to the occasion and new community hall was built in 1927.

This new community hall was for many years unconditionally available to the Women’s Auxiliary and was used for meetings, entertainment and special events. This still-impressive brick structure sits today as a private residence at the corner of Cockburn and Pearl Street in Berwick.

As Berwick grew, a second hotel was added and then several cheese factories were built, the first in 1884, and then another in 1893. The latter was one of the first Joint Stock Factories – a cooperative cheese making factory where each farmer bought shares and shared in the profits. Milk arrived daily by horse and wagon, and the cheese was shipped out, eventually by rail on the Ottawa & New York Railway (1897). This factory helped Berwick retain its role as an agricultural centre and paved the way for Kraft to establish a factory in 1929.

As the settlement grew, so did the demand for churches. The first, a Methodist church, was established in 1883. This church became the United Church in 1925 and, while no longer in existence in Berwick, it is remembered today on the Cairn near the village’s four corners.

As for schools, the Cockburn brothers built a school in the early days of the settlement and another was constructed in 1880 as the community grew. The most obvious school in Berwick was in the building that still sits today on Union Street. The original Union School was replaced by a new modern school on Cockburn Street in 1964. For several years the building housed the municipal office for Finch Township, and later North Stormont.

The original Union Street school building construction date is not known but could likely have been part of a school moved from Finch to Berwick in 1917. Given the architecture of the Union Street school, it likely was used in the early 1920’s and after until the students were moved to the new building in 1964.

The Railway Era

The arrival of the railway prompted a boom in the local economy. While important, the arrival of the Ottawa and New York Railway in 1897 did not have the same impact as those in other nearby locations, such as Avonmore or Newington. Berwick had a small one floor station, situated near the Union Street school. There were two passenger trains daily in each direction, but the primary impact was from the four to five freight trains that loaded milk, cheese, grain and lumber products en route to Ottawa or even New York City. Another hotel was added at this time and sales folk came by train to display their wares for local merchants to purchase.

In the early 1900’s, the population of Berwick reached 250. Like so many other Eastern Ontario villages it was the boom time but slowly it began to show decline as road transport replaced rail.

What Happened to the Mill Pond?

The story of how the mill pond area in Berwick changed over time is really the story of how a tiny industrial hamlet evolved into the quiet rural crossroads it is today. That early surveyor’s map is a snapshot of Berwick at its most ambitious moment—when the sawmill, the mill pond, and the Cockburn family’s enterprises were the beating heart of the place. From there, the landscape began to shift.

In 1864 the Cockburn sawmill burned to the ground. Sadly, it was not replaced, as the demand for lumber was declining and competition for the provision of lumber increased.

Many sawmills also began to move to more reliable steam generator power. New mills with steam power were suddenly appearing throughout Eastern Ontario communities. (A steam power mill was built west of the village in 1895).

Water‑powered mills, affected by seasonal changes in water flow, became less competitive when steam driven units could continuously maintain consistent production. These steam powered units simply required access to water rather than to the amount of flow. In the area around the South Nation River watershed, the larger river became more regulated and this adversely affected the potential flow of the Payne River. As was the case in nearby Avonmore, the mills on the Payne River began to disappear.

Berwick’s influence in the timber trade declined with the closing of the mill, while close-by communities like Crysler and Finch began to grow at its expense.

As the Cockburn mill business activity stopped, the associated mill pond was no longer essential. Without active management, the pond began to fill with sediment, the dam fell into disrepair, and suddenly the pond became a marsh. Eventually it transitioned back to a slow, shallow stretch of creek. Over time, much of the pond land became pasture, meadow and treed area next to the remaining river channel.

Google Satellite Image (2026) – Today The Mill Pond is Gone

Recent History – Late 1900s–Present

When the Railway tracks were removed in 1957, it was the end of an era for many communities like Berwick. The commercial core had already shrunk in the village as automobile travel displaced train travel. Businesses had also moved to the larger nearby communities of Finch and Crysler.

Recently the Cooters general store and automobile repair location, a major landmark in Berwick for many years, moved to Crysler. The building remains today in an obvious unused condition at the major four corners of the community, a sad reminder of the village’s business decline.

For many years the Kraft plant remained in Berwick, but in the 1960’s Kraft consolidated its operations here and in Newington as well, moving to its plant to Ingleside.

With the reorganization of Finch township in 1998, it looked like Berwick would no longer retain its municipal centre status that it had held since 1850. However, Berwick kept its location role, and today it is the administrative centre for North Stormont Township. Until last year, the offices were in the Union Street school building, but now those municipal offices have moved to the vacant school on Cockburn street.

Final Words

Berwick has always been a place that punches above its weight. From the Cockburn sawmill to the cheese factories, from the railway era to its long role as the municipal centre of Finch Township, this small village has continually adapted to the shifting currents of Eastern Ontario life. Even when the railway disappeared in 1957, when businesses moved to larger centres, and when Kraft consolidated its operations in the 1960s, Berwick remained anchored by the families that have lived there for many generations.

When Ontario restructured its municipalities in 1998, Berwick retained its seat of responsibility in the new Township of North Stormont. It’s a quiet testament to the village’s enduring importance.

Today, little remains of the mill pond that once powered Berwick’s earliest industry. The dam is gone, the water has settled back into a quiet ribbon of creek, and the land that held the pond has returned to meadow and pasture. Yet the story of that pond — and of the people who depended on it — still remains in the minds of village residents and those in nearby areas.

The mill pond may be gone, but the landscape still carries the imprint of the community that grew around it. Berwick’s history can be observed in its streets, its river, its community centre, its old schoolhouses, and its Cairn (Gaelic word: a man‑made pile or mound of stones usually built to mark a place of significance. It’s quite fitting for its prominent location at the four corners of Berwick).

Like so many villages in Eastern Ontario, its past is subtle — easy to miss unless you know where to look — but it still reflects its long history and the stories of the families who have lived there for generations.

Postscipt: My Continuing Study of History in Eastern Ontario

I am reminded, as I continue to study villages in Eastern Ontario, of a phrase that my University history professor regularly repeated to our classes years ago: “History is never made up of things that might have been.” That statement is true for recorded history of course, but what I often find is that little of the history of Eastern Ontario has become verifiable recorded history. Much of the local history, then, must be left to detective work, and often to imagination.

What I described in this piece includes a good deal of recorded history, but some elements of my own detective work, mixed with imagination. Much of the latter is becoming more realistic of true events, I believe, the more I study village life in Eastern Ontario.

[i] Historical Atlas of Counties: Stormont Dundas Glengarry. H.Belden & Co. Toronto. 1879.

[ii]Pioneer History Finch Township. Authors: Finch Teachers. September 1957. Locally published and held by the Stormont Dundas Glengarry Library. We can be thankful to the teachers and students from schools in Finch Township who ardently put this document together, but to schools in other Eastern Ontario villages where teachers have worked with students to capture local histories, and whose works remain unpublished but available locally today.